I used to have my 2.3% rule. Because of relative population decline, it is now my 2% rule. Let me educate folks who haven’t heard of this rule.

Over the years, every time I would ask someone why New Brunswick doesn’t have more NHL hockey players or Olympic athletes or unicorn startup companies or star academic researchers or Giller Prize winners, patents filed, or [fill in the blank], the answer would always be we are a small province, what do you expect?

That’s when I came up with the 2.3% rule. At the time, New Brunswick was home to 2.3% of Canada’s population so why was it unreasonable to assume the province could have at least 2.3% of something?

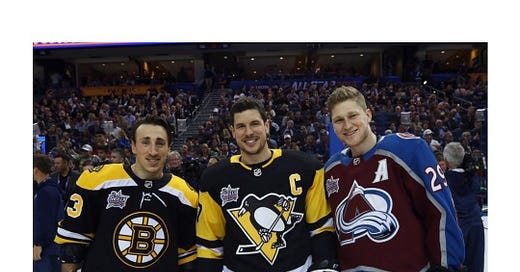

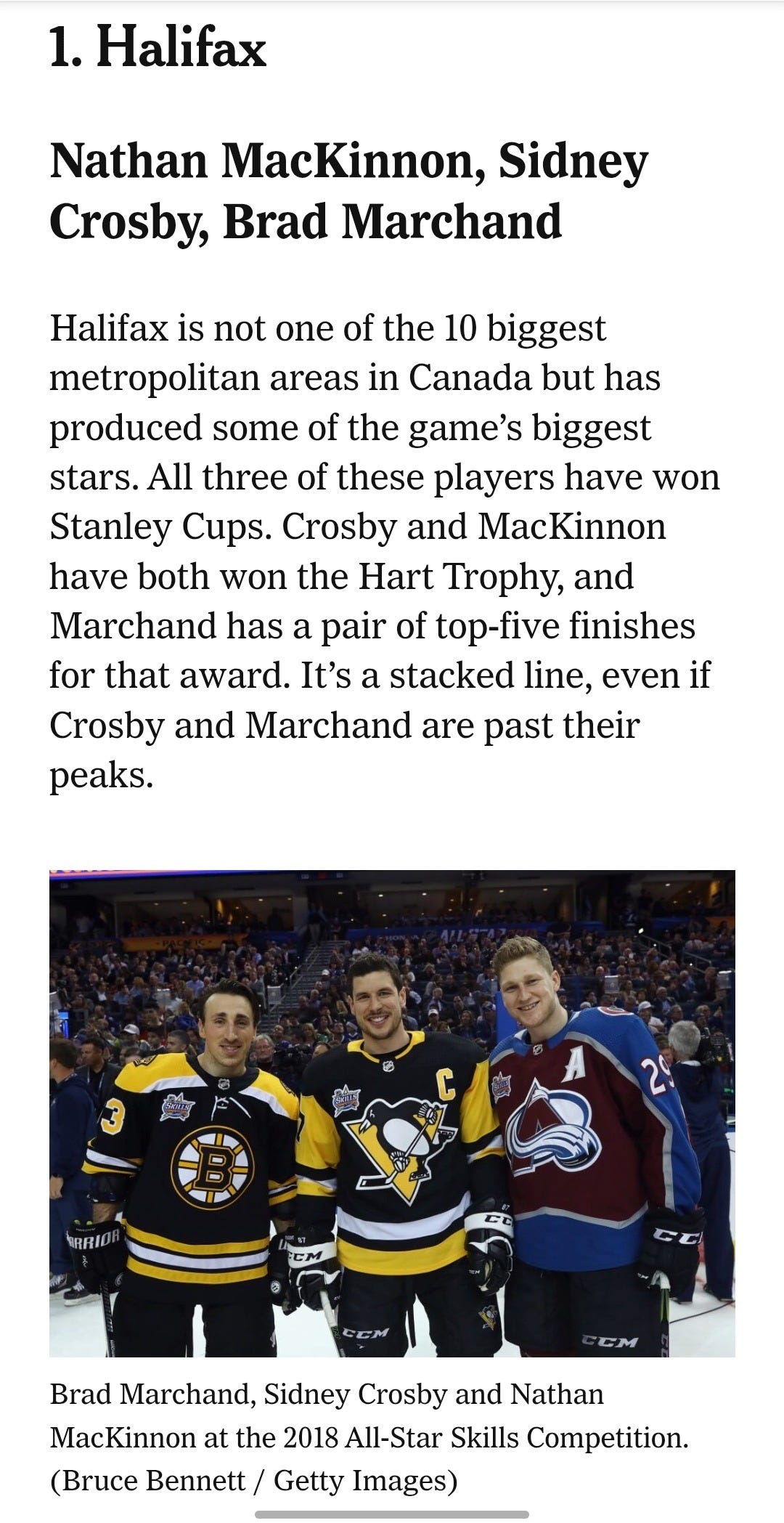

Consider Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia has 2.6% of Canada’s population and its capital city has produced what The Athletic calls the top hockey trio of any city in the world including Moscow and Toronto.

I’m not going to go through a list of comparisons between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick but the question remains.

A deeper dive reveals maybe a little more insight into why we don’t have an “own the podium” culture in New Brunswick. I have been told by many inside and outside government over the years one problem is the “spreading the money around” problem. The logic goes like this: we have lots of demands on government funds (sports, culture, small business, rural, etc.) so let’s spray the limited government money around and make sure everyone gets a little but not enough than anyone organization gets ahead. Worse, if an organization starts to do well then “they don’t need the support anymore”.

This definitely applies in the world of economic development. If you need $10,000 for a new startup, small business, or as researcher with a cool idea or an economic development group that wants do to something innovative, no problem. If you need $500,000. Big problem. I see this in agriculture and in many other sectors. Dribble the cash around. Make sure everyone gets a taste. Ensure that no one really takes off.

Another reason I hear is the ‘leveling down’ culture. This is particularly evident in the K-12 education system (at least the English system) where there is very little done to tease out and push hard the most talented students. In my world, the top high school kids at math from around the province could be taking advanced calculus virtually offered by a UNB prof.

I think you might find similar levelling down in health care and other areas of our society if you looked closely.

How do you get more of the 2%? Shouldn’t this be the question driving economic development questions but also society in general? How do we get 2% of Canada’s top academic researchers at our universities. I’m not greedy - maybe I’d stretch it to 3%.

People will say we don’t have the assets - the hockey schools, the research institutes, the cultural entities. I’m not about that.

Take bilingualism. New Brunswick is the only bilingual province in Canada (French and English). We have a program at UdeM that turns out translators. The public and private sectors spend millions of dollars each year on translation. Have we levered this ‘asset’ into economic development? Have we become a national centre of excellence? Do we have top, global firms here developing cutting edge translation tools?

I’m not sure but I do know that according to Statistics Canada, there is only one firm in the translation and interpretation services industry in New Brunswick with 10 or more employees. One. We used to have more. 2% rule? Nope. Even in this area with all the natural advantages we have 1% of the firms with 10+ employees.

How do you ‘level up’ or ‘own the podium’? Focus. Investment. Leveraged bets.

We need to start taking the 2% rule seriously.

As someone who "came from away," I see so many incredible things about this province—things that locals often take for granted. As you might have guessed, I'm a once-removed Ontarian, and I absolutely love it here. My only regret? Not making the move sooner.

New Brunswick has so much to offer, but one thing continues to hold it back: mindset. That said, I believe this is starting to change. The shift began, in part, with the ousting of Higgs, signaling a broader movement toward progress.

Someone once asked me why Ontario seems to win all the major lottery jackpots. The answer is simple: numbers. With the largest population in the country, the odds are naturally in Ontario’s favor.

If we want to improve New Brunswick’s representation in all areas—economic growth, infrastructure, and opportunity—we need investment. But securing government funding is a competitive process, much like triage in an emergency room. Another way to unlock resources is to reallocate spending from areas where it's not essential.

Take, for example, our three international airports—Fredericton, Moncton, and Saint John—all within an hour and a half of each other. With a population of less than a million, do we really need all three?

Fredericton, as the capital, makes sense—it’s centrally located and serves as a government hub. Moncton is a key economic driver, home to a thriving warehousing sector and aviation schools. But Saint John? With its major shipping port and frequent fog disruptions, it’s the Chicago O’Hare of the Maritimes—a hub that’s often unreliable. Wouldn't those resources be better invested elsewhere?

Continuing with the theme of unreliability, let’s talk about NB Power. With limited heating options, it essentially holds a monopoly. Ontario Hydro had its fair share of issues too, but Ontarians didn’t tolerate that kind of inefficiency—and neither should New Brunswickers. Can someone explain to me what ever happened to natural gas in this province?

One way the provincial government could cut costs and modernize is by investing in solar power. By outfitting government buildings with solar panels, NB could reduce long-term energy expenses while positioning itself as a leader in renewable energy. Additionally, the province should expand residential solar power grants to match those in PEI, making clean energy more accessible to homeowners.

There are also efficiencies to be gained in public transportation—starting with school bus routes. Consolidating routes could cut costs in half. Yes, this would mean French and English-speaking students sharing the same buses. But let’s be honest—English is the global business language, whether we like it or not. Even in China, it’s the most widely learned language.

New Brunswick has an opportunity to break free from outdated systems, invest in smarter solutions, and create a more sustainable, efficient future. The only question is—will we take it?